Making a three minute video about a garbage can initiated me into Madison’s campus film community. Watch Survival Supplies (1989) and read about what I learned from the experience.

Okay. So Who Cares?

A lot of people make videos when they’re 19 years-old. Way more do so now, in fact, with the potential for far greater reach and impact thanks to social media. Why should I bother writing an entry about a video shot and edited on VHS over 30 years ago? Why should anyone want to read it?

Well, part of the mission of this website is personal. I’m looking back for inspiration as I work on projects in the future. Revisiting work made years ago has reconnected me with the creative spirit that drove me back then. So that’s what I’m getting out of it, regardless of whether anyone reads this. Perhaps naively, I hope that others might find inspiration to get out and make something, too.

This website also discusses moving images in Madison (and Wisconsin, and the Midwest). Telling the story of Survival Supplies helps to revisit people and organizations who have been part of that story. Throughout this post I’ll swiftly alternate between fine grained details about my personal experiences and broader observations about people and organizations in Madison’s film community.

I wasn’t fully a part of that community quite yet in 1989. My experience with Survival Supplies helped me find it.

Follow the Instructions

At the time, I worked a few hours each weekday at the Glenway Pharmacy, near the Glenway Golf Course. Tom Gitter owned and operated the Glenway Pharmacy for many, many years before I started working there. A neighborhood pharmacy could be owned and operated by one pharmacist back then.

A metal drum stood behind the candy counter and cash register at one end of the store. The drum had writing on the side of it. During a particularly slow shift, I tipped the drum a bit so that I could read it. The Office of Civil Defense issued the drum to store “survival supplies.” The text provided instructions for using it in various contexts.

Based on current eBay listings1 for similar vintage survival supply drum barrels, I’m guessing that the Glenway Pharmacy drum likely dated back to the 1960s.

The matter of fact instructions, to be used in horrifying conditions, fascinated me. But the eventual images in Survival Supplies did not act out the instructions. Instead, the text inspired a series of images arranged by the principles of free association, repetition and variation. Once I made an association between water and a green shake (remember this was March, so Shamrock Shake season), it was an easy, if somewhat gross, leap to a chocolate shake for the commode section. That, in turn, led to the strawberry shake and the association with Pepto Bismol.

I asked Mr. Gitter if I could borrow the garbage can for the weekend. He let me use it without asking for any details. I shot most of the footage with the can inside the house that I grew up in on Birch Avenue. My friend Dave Sather, who appeared in earlier films and videos, assisted me.

I shot Survival Supplies with an RCA CC010 Color Video Camera.2 My family had an RCA VHS deck that had a portable section with a 14-pin input for that video camera. I had used the camera and deck on several high school era videos. Like many tube cameras, the CC010 suffered from burn-ins and ghosting. This was usually a problem when I wanted a clean image. But I used the flaw to my advantage in Survival Supplies. I let the Civil Defense logo burn in before it panning between the two logos. The ghost logo floats across the screen until it comes to rest on top of the other logo.

The various screen sizes and mattes were created with a cheap Radio Shack gizmo. I composed the screen shapes as I shot them, not in post.

I shot exteriors with the gutters and straws at the intersection of Glenway Road and Paunack Avenue. The Glenway Golf Course visible in the background. My home block on Birch Avenue did not have curbs and gutters. We had to walk over to Paunack to find streams of water strong enough to carry the straws.

I temporarily had access to a video editing suite belonging to a local DJ company. Access was supposed to be in exchange for logging footage or relatively menial editing work related to their wedding videos. I’m ashamed to admit that I did not stick around after the Survival Supplies edit was complete.

A Freshman Finds His Way

My undergraduate years at UW-Madison started in Fall 1988. I made Survival Supplies in Spring 1989, before I was able to take film and video production classes. But I had attended my first few meetings of the Independent Film and Video Collaborative (IFVC).

Eventually, I visited video production professor Laura Kipnis during her office hours. I asked her to take a look at Survival Supplies. She granted me permission to enroll in Introduction to Film and Video Production (CA 355) the following semester, Fall 1989.

My first IFVC meetings had a direct influence on Survival Supplies. I saw recent and historical avant-garde and experimental films at meetings. Influences included the unconventional voice over in Christopher Maclaine’s The End (1953) and the performance style in George Kuchar’s weather diaries. I believe I first saw Weather Diary 4 (1988), shot in Milwaukee. Most viewers assume that the “17 1/2 gallons” voice is supposed to be Elmer Fudd. But that voice is actually a 19-year-old midwestern kid attempting to mimic (but not exactly impersonate) an introspective George Kuchar3.

Survival Supplies taught me that an important part of experimental film and video making was actively participating in a community. Production itself was something that I could do on my own with relatively few resources. The distribution and exhibition side, on the other hand, depended on my willingness to put myself out there and get involved with groups like IFVC.

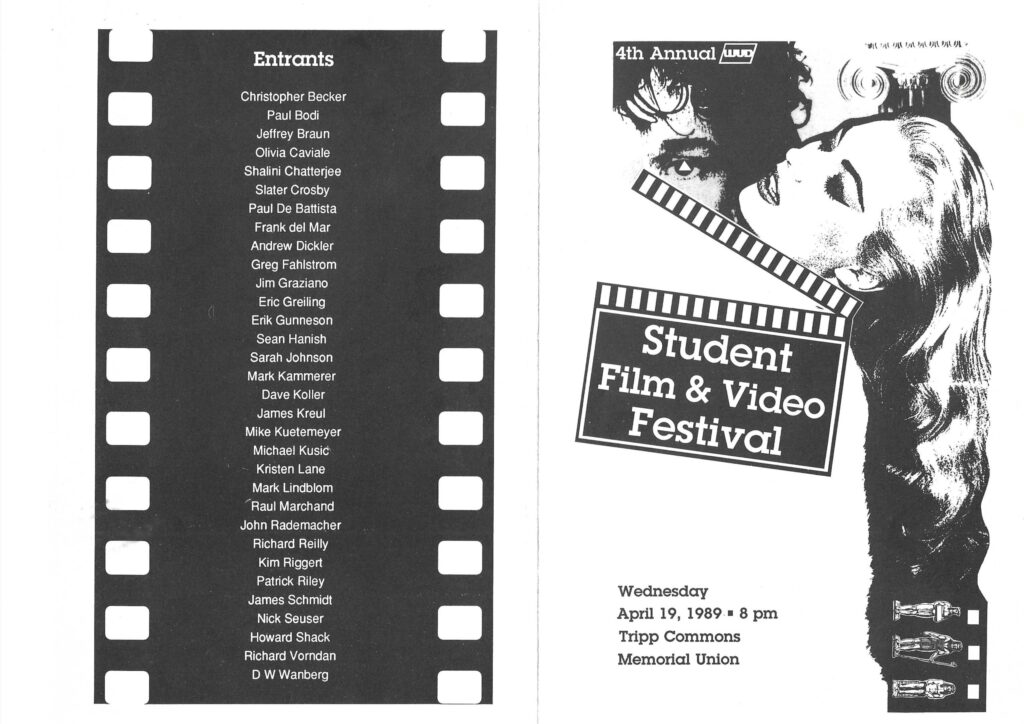

Survival Supplies probably premiered at the Spring 1989 IFVC Open Video Show. This was my entryway into the campus film and video production community. But two additional screening opportunities that spring also opened some doors for me. The fourth annual Wisconsin Union Directorate Student Film & Video Festival introduced me to the larger campus film community. The Wisconsin Media Artists Showcase in Milwaukee in 1990 introduced me to a larger regional filmaking community.

Fourth Annual WUD Student Film & Video Festival, April 19, 1989

The Wisconsin Union Directorate is the student programming board for the Wisconsin Union. As their mission states, they are “the students who organize, promote and execute some of the best experiences and events you can get outside the classroom.” WUD is probably best known for its music committee. The film committee also has had a lasting impact on Madison’s film culture.

I’ll return to WUD film many times on this website. For now I’ll focus on my first experience with the WUD Student Film & Video Festival.

Student run exhibition of student films and videos seems to be missing from current student film culture in Madison. Often, a filmmaker wants to show his/her own work, and then their interest in exhibition wanes shortly after that.

Building a film and video community starts with having consistent opportunities to exhibit work. Regular screenings eventually influence the production of new work. Filmmakers know that they’ll have an opportunity to share their films with a receptive audience.

I didn’t make Survival Supplies for a class. I knew that I’d have a chance to screen it at least at an Open Show. And I knew that I had the opportunity to submit to the WUD Film festival. Those opportunities motivated me to make Survival Supplies in the first place.

As you’ll see from the program, I was one of 32 entrants that year. From a 2023 perspective, it should stand out that only 5 out of 32 of the entrants were female. That’s about 6%. The gender gap in film production has improved, but not by much in some areas. According to the Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film at San Diego State University, in 2022 “women comprised 26% of directors, writers, producers, executive producers, editors, and cinematographers,” and “women accounted for 8% of cinematographers.”4 So when I talk about creating opportunities, we should all keep in mind that there are cultural and institutional obstacles to creating equitable opportunities in film production and exhibition to this day.

That said, there are several names worth pointing out on the list of entrants. For example, after graduating in 1990, Andrew Dickler worked as an apprentice editor on Pulp Fiction. He then went on to work with filmmakers like Miranda July and Christopher Guest.5

Four names on the list will appear on this website many times: Sean Hanish, Mike Kuetemeyer, Erik Gunneson and D.W. Wanberg. Each of them was invovled with the IFVC.

Sean Hanish has directed features like Return to Zero (2014) with Minnie Driver and Saint Judy (2018) with Michelle Monaghan. Mike Keutemeyer is an Assistant Professor in film and media arts at Temple University. Erik Gunneson has been teaching film production in the Communication Arts Department for many years.6 And, of course, D.W. Wanberg has a long history in film and public access video in Madison. He worked with Leon Varjian on The Vern & Evelyn Show in the early 1980s, and makes his own D.W.’s Show to this day.7

On the WUD Film Committee side, Mike Maggiore served as the Master of Ceremonies for the evening. I did not know Mike. In 1989 he was wrapping up his time as a student at UW-Madison. In 1992, when he was working at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, he returned to be a judge for the 7th Annual Student Film & Video Festival. More on that below. In 1994, Maggiore started working alongside Karen Cooper at the Film Forum arthouse and repertory cinema in New York. In 2022, he was named the artistic director of Film Forum.8

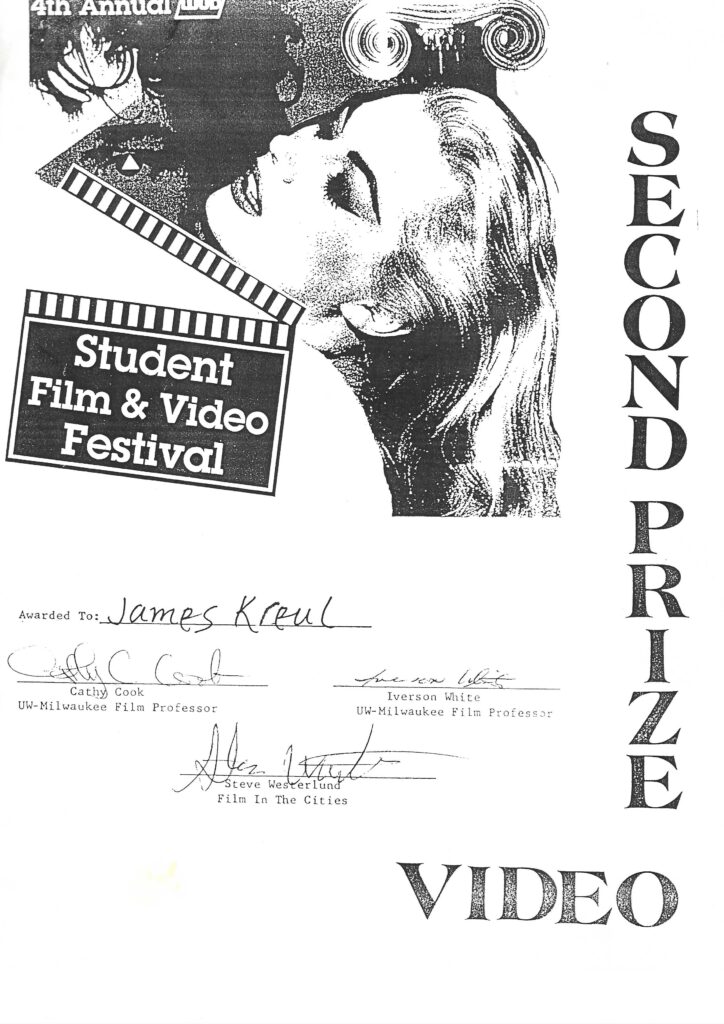

While I did not meet the judges, their participation helped me learn about the independent film landscape in Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Two UW-Milwaukee film professors served on the jury: Cathy Cook and Iverson White. I’m not sure how I never got to meet Cathy Cook while she was in the Midwest, but I admire her work. Her great film The Match That Started My Fire (1992) was selected to be preserved by a Avant-Garde Masters Grant in 2021. She also appears in several George Kuchar videos, including Weather Diary 4, mentioned above. Iverson White received his M.F.A. from U.C.LA. during the period associated with the L.A. Rebellion. In 1992, he directed a feature film, Magic Love, with grants provided by the National Endowment for the Arts and Film in the Cities.

The third judge was Steve Westerlund from Film in the Cities in Minneapolis/St. Paul. It has been years since I have thought about Film in the Cities and its significant impact on filmmaking in the Midwest. It should not be forgotten. You can find a historical overview of FITC from 1970 to 1993 at the Walker Art Center website.

It is worth remembering that for a while, with funding provided by the Jerome Foundation, FITC provided film production grants to filmmakers in Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas. (This ended when the Jerome Foundation returned to its mission to support artists specifically in Minnesota and New York City.) Just the idea of such a grant was inspiring. At some point I even applied for one, which reinforces my argument that opportunities can and will inspire creativity.

More Than a Prize

So . . . how did the evening of April 19, 1989 in the Tripp Commons go?

Survival Supplies was awarded the Second Prize in the video category. (This was the third tier, behind Grand Prize and First Prize.)

This was a surprise, and very exciting. It encouraged me to continue creating.

I did earn a laugh during my acceptance remarks. I thanked my mother for assisting me with my nude scene. That’s me sitting in the can at the start of the commode sequence, and Mom hit record and zoomed out for that shot.

I did not win a Student Film & Video Festival prize again until my last opportunity, at the 7th edition in 1992. That year I won the top prize for a 16mm optically printed found footage collage called Autobiograffti. There are interesting connections between the 4th and 7th Festivals.

Who were the judges in 1992, you ask? Cathy Cook, Mike Maggiore, and a different representative from Film in the Cities, Margaret Weinstein. Did Cathy remember my name from Survival Supplies? Did Mike remember my acceptance speech joke? Probably not. But I like to think that they did.

Wisconsin Media Artists Showcase in Milwaukee, May 5, 1990

There have been several attempts to improve communication and collaboration between filmmakers in Madison and Milwaukee over the years. Communication waxes and wanes. There were efforts to network with Milwaukee filmmakers leading into the 2000 Wisconsin Film Festival, for example. Now, with the Milwaukee Film Festival also taking place in the Spring, and the Milwaukee Underground Film Festival actually taking place on the same weekend as the Wisconsin Film Festival, I think it is fair to say that the Wisconsin Film Festival is no longer a catalyst for that kind of cooperation.

Great Lakes Film & Video was an organization based in Milwaukee which perhaps aspired towards something like Film in the Cities, to showcase films and provide support for filmmakers in Wisconsin. It is not easy to reconstruct its history from the internet, so I will update this section after I talk to probably anyone in Milwaukee.

As early as 1985, Mary Yelanjian was listed as director of Milwaukee’s Great Lakes Film and Video Center in Chicago Reader coverage of a screening of independent films from Wisconsin. At some point Yelanjian and Great Lakes Film & Video selected films for Milwaukee’s Latin American Film Series.9 As late as 1993, Yelanjian discussed in Art Muscle an upcoming Great Lakes Film & Video screening of highlights from the Women in the Directors Chair Film Festival.10

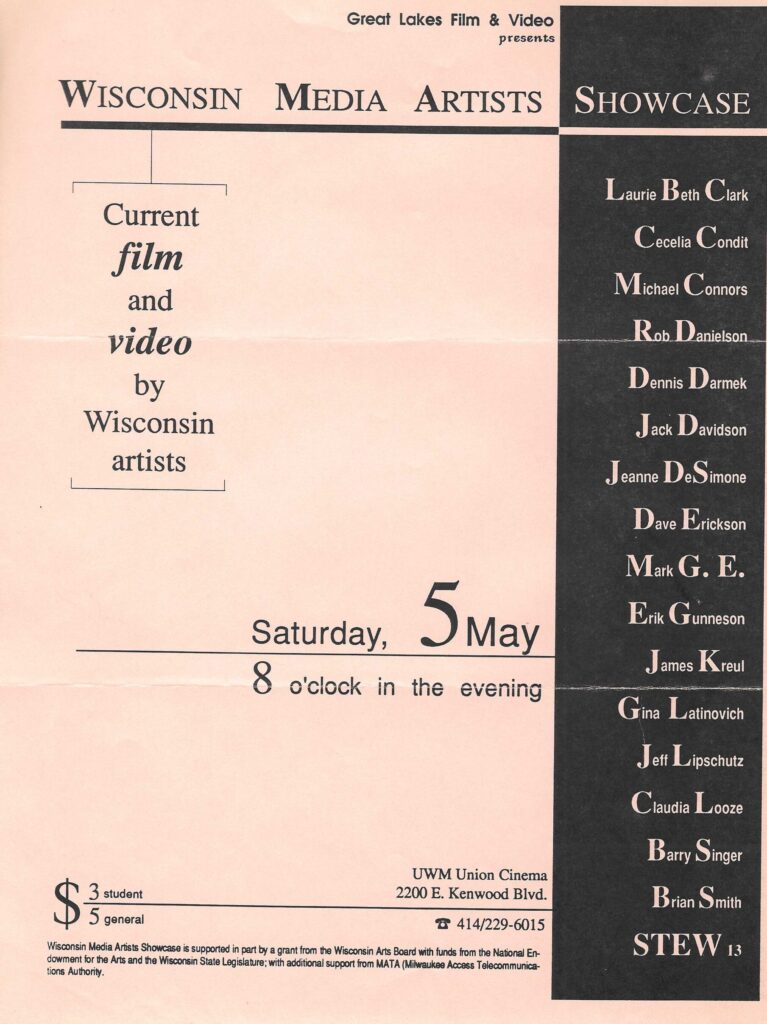

In spring of 1990, Great Lakes Film & Video initiated a call for entries for a Wisconsin Media Artists Showcase, to be held at the UWM Union Cinema on Saturday, May 5, 1990. They received a grant from the Wisconsin Arts Board and additional support from Milwaukee Access Telecommunications Authority (MATA).

There was some communication between film departments in Madison and Milwaukee at the time. For example, since Madison had a 16mm reversal color lab, and Milwaukee had a 16mm reversal black and white lab, there was a film exchange so that students at each campus could shoot either color or black and white. But, as would be the case in 2000 with the Wisconsin Film Festival, and as is the case again now, there needed to be more of an ongoing exchange of ideas and films. The Wisconsin Media Artists Showcase was a potential solution to address that.

Survival Supplies was selected for the Showcase, as was work by fellow IFVC member Erik Gunneson.

I was honored to be in a screening that also included Cecelia Condit, whom the IFVC had just featured at the Women Video-Maker Series at the Madison Art Center a month earlier.

The selected artists included some professors and faculty, like Laurie Beth Clarke from the Art Department at UW-Madison, and Rob Danielson at UW-Milwaukee.

I found a letter from Yelanjian and Great Lakes Film and Video from January 1991 which refers two two GLF&V projects that attempted to build a community of Wisconsin filmmakers. I had responded to a questionnaire for a Wisconsin Media Artists Directory, and had expressed interest in participating in a Wisconsin Teacher Video Rental Program. The directory was one of several attempts to create a single resource to contact film and video artists and professionals across the state. (My memory is fuzzy, but. I believe that the Wisconsin Film Office had one, too.) I had completely forgotten about the proposed rental program, but the letter outlined its goals.

This program would allow elementary and secondary teachers to rent videos at reduced rates for classroom use. Great Lakes Film & Video is now organizing a VHS videotape library with an accompanying catalog to get this program off to a strong start. In addition, GLF&V would use this library as a tool for creating touring programs and compilation tapes of work by Wisconsin artists.

Letter from Mary Yelangian, Managing Director, GLF&V, January 25, 1991

I don’t recall submitting work to the proposed library. It was a very interesting idea, one that probably makes more sense now with downloading digital files. The logistics of curating programs, artists fees, and file security would be a challenge, but the general idea is one that might be worth revisiting.

Returning to the Wisconsin Media Artists Showcase, there are names on the screening list with whom I would be in contact again for the Wisconsin Film Festival a decade later. Mark G.E., for example, premiered Midwestern Gothic at the 2000 Festival.

Another Wisconsin Film Festival connection was someone who was not on the list, but was in attendance. Chris Smith’s American Job, completed in 1996, was an opening night film at the 2000 Wisconsin Film Festival. At some point during our conversations during the Festival, the Wisconsin Media Artists Showcase screening came up. He remembered seeing Survival Supplies, ten years earlier, which made me very proud.

Conclusion

A few takeaways, now that writing this has stirred up a lot of memories.

First, I’m inspired to continue making stuff. Sometimes I forget what got me started on all of this. I like the kid who made Survival Supplies, and I’d like to spend more time with him.

Second, I’m more motivated than ever to continue the Project Projection screenings at Mills Folly Microcinema. A few filmmakers have asked me about the August 18 early deadline (coming up!), because they’re working on something with the intent to screen it at Project Projection on September 20. That’s the way it should be happening in this town.

Third, I need to work harder on networking with Milwaukee and other microcinemas in Wisconsin. We’ve made some progress, but writing this has reminded me that the progress can slow down or reverse unless attention is paid to networks and relationships.